ВЪЗМОЖНОСТИ ЗА УЧАСТИЕ В ТРЕНИНГОВИ ПРОГРАМИ И ИНИЦИАТИВИ,…

ANIDOX:LAB 2023 ANIDOX:LAB е персонализиран професионален курс за творци, режисьори, продуценти…

Literary Translations is a scheme of the Culture sub-programme of Creative Europe, supporting translations of works of fiction from one European language to another. Unlike other similar programmes, project costs may include translation, publishing, dissemination and promotion of books. For this reason writers visit the respective countries to meet their new readers.

In December 2019, for the presentation of her book “Balkanalia. Growing Up in Times of Transition”, Samira Kentrić herself arrived in Sofia. We are talking to Milen Milev of Paradox Publishing to learn more about the graphic novel of the Slovenian artist, as well as the project with which the publisher participates in the Creative Europe competition.

We found out about the novel in the most prosaic way possible nowadays – on the website of our colleagues from Beletrina, the Slovenian publisher of “Balkanalia”. We met with Beletrina a few years ago at a roundtable organised under the Creative Europe Programme at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

We didn’t know it for sure, rather we had hope, because this is a great book (I’m not just saying that because it was published with the Paradox logo). Otherwise, there are definitely books that we publish because of the idea that it is important to have them in Bulgarian, regardless of their commercial potential. As far as Bulgarian public is concerned, they lack liquidity in the first place in order to qualify as conservative or not.

“The barriers will fall, the people will remain.”

Samira Kentrić

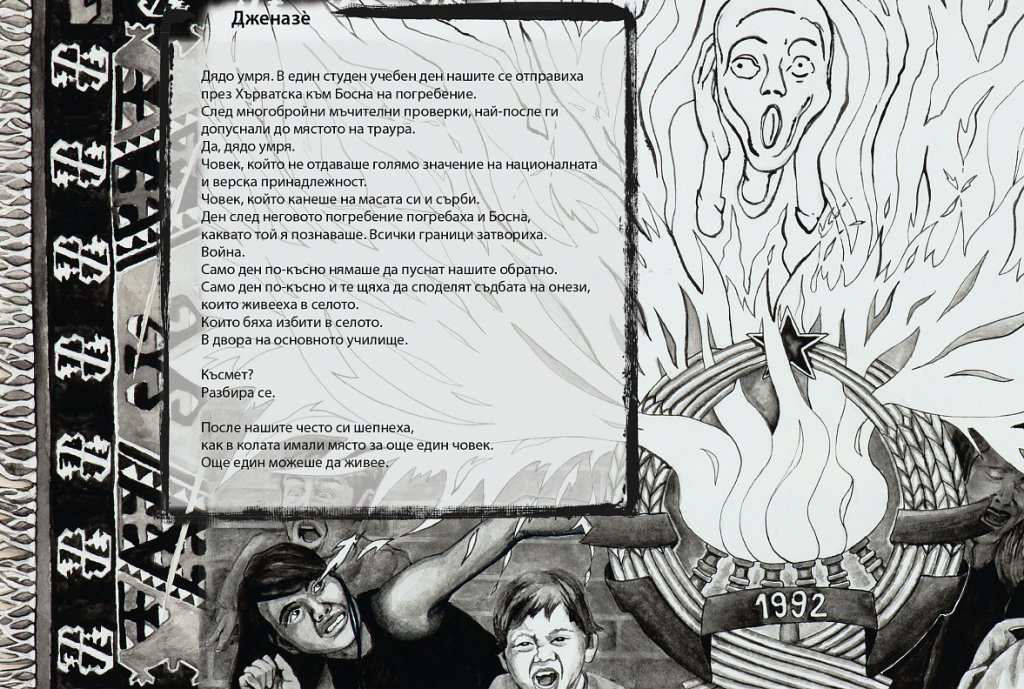

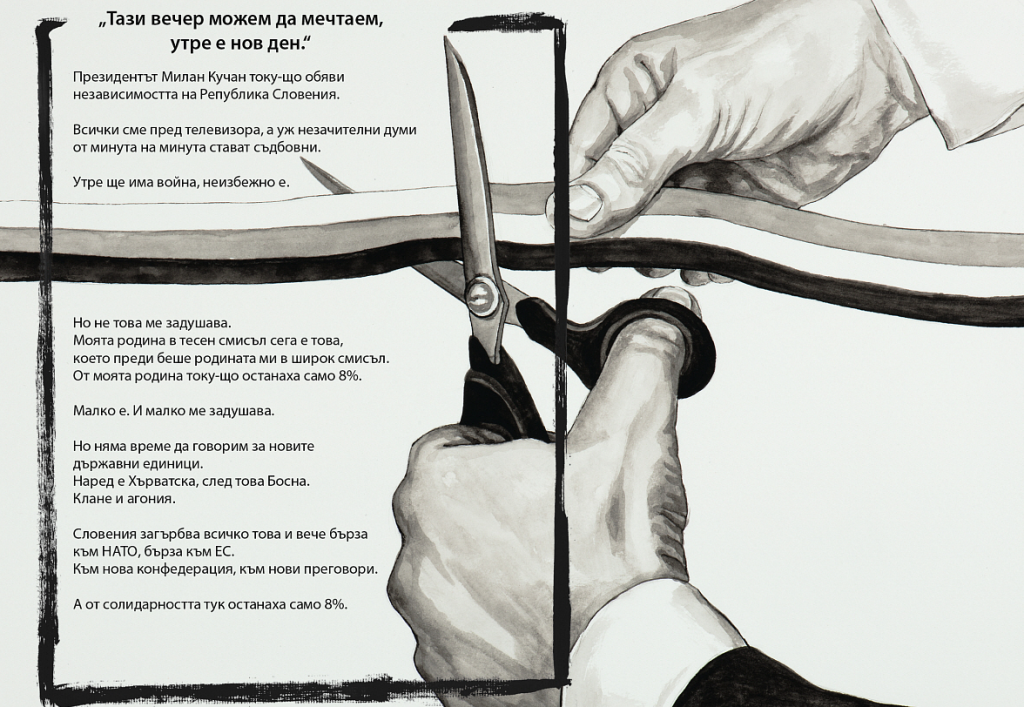

As far as mixed genres are concerned, a type of a “duet” of verbal and graphic signs, language is only part of the whole; in the case with “Balkanalia” – the smaller part. Samira Kentrić’s art is so powerful and multi-layered that it in itself represents “graphic poetry”, as Prof. Anri Kulev defined it at the presentation of the book. At the same time, the topics of the book are so universal, through the prism of the particular Yugoslav tragedy, that it does not matter whether the language is the “small” Slovenian, the“larger” Serbo-Croatian, or the “global” English. The challenge here was purely of polygraphic nature, starting with the non-standard album format of the book, to paper, printing, sewing, etc.

The first major motive of “Balkanalia” is that of roots and their loss. Samira Kentrić, however, does not see this as a bad thing; on the contrary, she promotes the idea that one must break free of the roots, go beyond the boundaries of the world around, look beyond. For her, this is not about losing identity – neither national nor personal – but about consolidating it by putting it in a global context.

The second motive stemming from the first is for crossing borders, for releasing the shackles, for breaking down the barriers. “The barriers will fall, the people will remain”, Kentrić herself says. In this sense, she is a firm supporter of the idea of a United Europe. Which doesn’t stop her from criticising the flaws in its implementation.

With enthusiasm from the audience and critics, with scepticism from the buyers.

“Balkanalia” is included in a list of books scheduled to be published in the first year of our ongoing three-year project under the Literary Translations scheme of Creative Europe. It bears the title “Thoughtful literature: the adultery of fact and fiction in modern European literature”. As a publishing house created by journalists, it is precisely the literature of fact, the interweaving of facts and fiction, the autofiction that interest us. In this sense, the autobiographical novel of Samira Kentrić is an ideal introduction to the whole package of 30 books. And at the same time – something different from the traditional novel and a decisive step towards so-called “unpopular/less popular genres”, the publication of which has been promoted by the Programme in recent years.

The hardest thing is to come up with a meaningful concept. In Europe, a large number of books of high enough artistic value is published annually to be approved for co-financing under the Programme – at least in theory. But three, five or ten books, as wonderful as they are, cannot compile a project – they have to have a common meaning, to serve a common goal, each of them to organically fit into the overall package of books you use to apply.

“Most of the fellow translators working on our European projects have been our partners and associates for years, not to say decades.”

I would say that our approach is of mixed nature – “top to bottom” and “bottom to top”, in the sense of a publisher looking for an author and an author making recommendations to a publisher. For over ten years, the interests of Paradox Publishing have been focused mainly on the literature of the Old Continent, and we are therefore striving to keep track of the current trends there. That’s where the original planning comes from. On the other hand, we have a set of favourite authors who put the concept of Paradox into words – I will mention here only Andrzej Stasiuk and Yurii Andrukhovych – and whose works do not just convey the European idea, but are, if necessary, its correction.

Co-financing programmes are definitely one of the ways. This is not just about Creative Europe, which is undoubtedly the largest in size – almost every country in the EU has a functioning programme supporting the translation and publication of the respective national literature – presumably non-commercial – abroad. Cultural exports are of prime significance and should be firmly embedded in any state policy.

To not give up until they have made a try. Of course, compiling a project takes time and energy. But at least direct financial risk is excluded as long as you have translation rights options and no need of perfect contracts for books that you would not have published without co-financing.

As a funny fact – we missed the most important part. The translators! We are talking about the Literary Translations scheme, which primarily insists on the quality of translation, so that our more or less “genius” publishing concepts are at the top of the spear of our translators. And for that, we must pay our respects. Most of the fellow translators working on our European projects have been our partners and associates for years, not to say decades. Creative trust between us is very high, which is essential for the final result. But that’s not unusual for the process of publishing. Rather, I would like to emphasise on the fact that there are many translators whose creative biographies have not only begun at Paradox, but are entirely made up of our books. In this respect, we pay particular attention to young translators and, over the years, we have set up our own in-house publishing system for their professional growth. We are pleased that this know-how was met with interest at the discussion on the development of Creative Europe with regard to the book sector, which was held in the framework of the Frankfurt Fair in 2019, and is likely to be part of the future recommendations for literary projects. We are also making our own contribution to the development of Creative Europe.